Approach to Training

As a career Health Scientist, I have long been a proponent of using sound training

principles and methods supported by evidence developed by the exercise science

research community. Through years of training and racing experience at a high

level and with an understanding of human physiology, I have been able to evolve

and refine a training approach that can be successful for any endurance athlete.

Fundamental to my approach is

periodization, or planning of the overall training cycle,

quality and specificity of training relative to volume and intensity, and

balance of training stress and recovery to facilitate adaptation

Over the years, I have looked critically at claims of “revolutionary” developments or

hyped fads in training that do not have any actual basis other than someone

reports it as the "latest and greatest." In essence, there have been no drastic

changes in what constitutes a sensible approach to training in recent years. Rather,

changes in training tend to come in small increments, and trends gradually develop

as the latest physiological research is absorbed into the mainstream..

Often, the practical physiological information provided by researchers simply

reinforces or helps explain why certain approaches to training in endurance sports

have been universally accepted by athletes and coaches over time. The research

helps define the physiological benefits that can be expected by the application of

various training methods.

For instance, it is well accepted that training for a specific event should emphasize

the conditioning of the energy systems involved in the performance of that

particular event. In other words, do in training what you plan on doing in racing.

What sometimes can be a source of controversy or confusion, however, is the

proper mix of training throughout a training cycle. Training periodization is a well-

established approach that helps address this issue.

Periodization

I am an advocate of periodization, an organized, planned approach in which an

overall training cycle (often a year) is broken down into shorter periods (weeks or

months). Each period has a different emphasis as to how training stresses are

applied. Periods are usually structured around the racing season and your goals

and purposes for competition.

The basic premise of periodization is this: reaching your maximum physiological

potential in competition can best be accomplished by varying training stresses of

frequency, intensity and duration during the periods leading up to important

competition. You build to your highest levels of performance at the right time by

adjusting the emphasis of the training and adaptation of the various physiological

systems during each period of the overall training cycle.

Periodization is useful for addressing the concern that you cannot maintain peak

physiological performance for extended periods of time without risking overtraining,

burnout, illness or injury. Thus, a key component of periodization is incorporation

of appropriate rest and recovery, not only at the end of a season, but throughout

the overall training cycle.

Quality versus Quantity

Continuous, high volume training for the sake of high volume too often can result in

overtraining, burnout, injury and a decision to leave a sport that is seen as too

demanding. Training too fast all of the time can have the same result. Training

should be of a quality and specificity to help you meet your goals and should be

based on current level of fitness, past experience, and your innate abilities. Each

athlete is unique.

Training needs to be individualized and workouts prescribed without overdoing

distance, time or speed to the detriment of athletic performance or overall well-

being. This is particularly important for the athlete with limited time to devote to

training.

That said, the key to training for endurance events is increasing both training

volume and intensity. Both are needed to fully maximize the development of the

aerobic capacity of the athlete. Below is a graphical depiction of the typical

relationship of volume and intensity during the overall training cycle leading up to

key races.

As the race season draws near and both volume and intensity have progressed,

volume is reduced in favor of even higher intensity training. Maintaining high

volume and high intensity for too long carries a much greater risk of overtraining

and injury. The reduced volume does not detract from overall fitness. Instead, the

purposeful higher intensity training at this time brings fitness to a physiological peak

in time for the key race(s).

Aerobic capacity can only be fully developed by adequately stressing the oxygen

delivery, oxygen utilization and the other physiological components that comprise

aerobic capacity. It is not simply a matter of going out every day and doing easy,

long distance training – long, slow distance trains you to go long and slow. Rather,

it is a complex process that requires a blend of easy to moderate endurance efforts,

shorter duration higher intensities of effort and properly timed recovery to allow the

body to adapt to the training. Included in an appropriate training program are

workout intensities that are designed to raise the lactate threshold (often referred to

as anaerobic threshold) and maximize VO2max (maximum capacity to utilize oxygen

in doing specific work).

Whether training for Olympic distance events (~ 2+ hours duration) or the Ironman

(~8+ hours), both are endurance events requiring a highly developed aerobic

capacity to maximize race potential. Ultra-distance events are raced at a slower

pace compared to the shorter events. Yet, improvements in lactate threshold and

VO2max result in more efficient and effective racing even at the longer distance.

Hence, intensity in training is still important to the overall racing potential of those

focused on the Ironman distance. The balance of intensity and volume will differ

somewhat, but the principles of training remain the same.

In my mind, there are three well-known triathletes whose accomplishments suggest

they were able to find the balance between volume and intensity for racing at

Olympic and Ironman distances.

Mark Allen: it took him several tries at the Ironman distance, but Mark was one of

the fastest Olympic Distance racers in the world and accomplished at the Ironman

distance with the fastest Hawaii Ironman from 1989 until 1996 (8:09).

Luc Van Lierde: the Belgian was one of the fastest Olympic distance racers in the

world in the summer of 1996, the same year he set the new Hawaii Ironman record

of 8:04 (and that included a 3 minute penalty!).

Karen Smyers: in 1995, she won the Hawaii Ironman and four weeks later won the

women's ITU World Championships, Olympic Distance, in Cancun, Mexico.

The bottom-line? Olympic Distance and Ironman training are not necessarily

mutually exclusive during the same season. The principles of training aerobic

capacity are the same, but the balance of intensity and volume at a given time

during the training cycle is shifted.

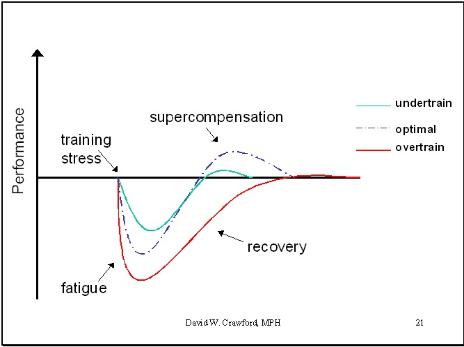

Training Stress, Recovery and Adaptation

An important piece of the puzzle is the balance of training stress and recovery to

allow the body to adapt to increased volume or intensity. As described above,

periodization integrates recovery throughout the training cycle. Below is a graph

illustrating physiological adaptation to a training stress when adequate recovery is

facilitated. It also shows how that response may vary for optimal, excessive and

inadequate training stress. Yakovlev uses the term supercompensation to describe

this adaptation.

Training places a physiological load on the body, resulting in fatigue and a decline

in performance ability. Improvement in performance can only occur with adequate

recovery. Inadequate training stress may bring only small improvement.

Overtraining requires excessive recovery and may not show any improvement.

Optimal training with adequate recovery results in improved performance abilities

due to the adaptive physiological/metabolic potential.

This model can be applied to all periods of the overall training cycle, whether an

individual workout, several days of building or longer periods of preparation. Of

course, one of the challenges of coaching any athlete is to find the right balance of

stress and recovery for each individual -- that's why coaching is as much art as it is

science.

Experience of the Athlete

The novice endurance athlete is better served by focusing initially on learning the

skills and gradually developing the aerobic capacity for the more modest endurance

events, e.g., Olympic distance or shorter. Intensity also needs to be constrained

until significant adaptation to training has occurred. Those skills and endurance will

be directly transferable to the longer distance as the body is able to adapt to

increasing volume.

For the more experienced and fit endurance athlete, the goal in training is two-fold.

First, significant training volume must occur within the typical low and moderate

intensities normally associated with endurance training. Second, higher intensity

training that addresses all of the physiological components of aerobic capacity must

be incorporated in a progressive, timely approach that allows for the highest quality

of training based on individual abilities. Both volume and intensity must be

tempered by planned rest and recovery. In this way, the probability of reaching

your physiological potential is maximized.

As a career Health Scientist, I have long been a proponent of using sound training

principles and methods supported by evidence developed by the exercise science

research community. Through years of training and racing experience at a high

level and with an understanding of human physiology, I have been able to evolve

and refine a training approach that can be successful for any endurance athlete.

Fundamental to my approach is

periodization, or planning of the overall training cycle,

quality and specificity of training relative to volume and intensity, and

balance of training stress and recovery to facilitate adaptation

Over the years, I have looked critically at claims of “revolutionary” developments or

hyped fads in training that do not have any actual basis other than someone

reports it as the "latest and greatest." In essence, there have been no drastic

changes in what constitutes a sensible approach to training in recent years. Rather,

changes in training tend to come in small increments, and trends gradually develop

as the latest physiological research is absorbed into the mainstream..

Often, the practical physiological information provided by researchers simply

reinforces or helps explain why certain approaches to training in endurance sports

have been universally accepted by athletes and coaches over time. The research

helps define the physiological benefits that can be expected by the application of

various training methods.

For instance, it is well accepted that training for a specific event should emphasize

the conditioning of the energy systems involved in the performance of that

particular event. In other words, do in training what you plan on doing in racing.

What sometimes can be a source of controversy or confusion, however, is the

proper mix of training throughout a training cycle. Training periodization is a well-

established approach that helps address this issue.

Periodization

I am an advocate of periodization, an organized, planned approach in which an

overall training cycle (often a year) is broken down into shorter periods (weeks or

months). Each period has a different emphasis as to how training stresses are

applied. Periods are usually structured around the racing season and your goals

and purposes for competition.

The basic premise of periodization is this: reaching your maximum physiological

potential in competition can best be accomplished by varying training stresses of

frequency, intensity and duration during the periods leading up to important

competition. You build to your highest levels of performance at the right time by

adjusting the emphasis of the training and adaptation of the various physiological

systems during each period of the overall training cycle.

Periodization is useful for addressing the concern that you cannot maintain peak

physiological performance for extended periods of time without risking overtraining,

burnout, illness or injury. Thus, a key component of periodization is incorporation

of appropriate rest and recovery, not only at the end of a season, but throughout

the overall training cycle.

Quality versus Quantity

Continuous, high volume training for the sake of high volume too often can result in

overtraining, burnout, injury and a decision to leave a sport that is seen as too

demanding. Training too fast all of the time can have the same result. Training

should be of a quality and specificity to help you meet your goals and should be

based on current level of fitness, past experience, and your innate abilities. Each

athlete is unique.

Training needs to be individualized and workouts prescribed without overdoing

distance, time or speed to the detriment of athletic performance or overall well-

being. This is particularly important for the athlete with limited time to devote to

training.

That said, the key to training for endurance events is increasing both training

volume and intensity. Both are needed to fully maximize the development of the

aerobic capacity of the athlete. Below is a graphical depiction of the typical

relationship of volume and intensity during the overall training cycle leading up to

key races.

As the race season draws near and both volume and intensity have progressed,

volume is reduced in favor of even higher intensity training. Maintaining high

volume and high intensity for too long carries a much greater risk of overtraining

and injury. The reduced volume does not detract from overall fitness. Instead, the

purposeful higher intensity training at this time brings fitness to a physiological peak

in time for the key race(s).

Aerobic capacity can only be fully developed by adequately stressing the oxygen

delivery, oxygen utilization and the other physiological components that comprise

aerobic capacity. It is not simply a matter of going out every day and doing easy,

long distance training – long, slow distance trains you to go long and slow. Rather,

it is a complex process that requires a blend of easy to moderate endurance efforts,

shorter duration higher intensities of effort and properly timed recovery to allow the

body to adapt to the training. Included in an appropriate training program are

workout intensities that are designed to raise the lactate threshold (often referred to

as anaerobic threshold) and maximize VO2max (maximum capacity to utilize oxygen

in doing specific work).

Whether training for Olympic distance events (~ 2+ hours duration) or the Ironman

(~8+ hours), both are endurance events requiring a highly developed aerobic

capacity to maximize race potential. Ultra-distance events are raced at a slower

pace compared to the shorter events. Yet, improvements in lactate threshold and

VO2max result in more efficient and effective racing even at the longer distance.

Hence, intensity in training is still important to the overall racing potential of those

focused on the Ironman distance. The balance of intensity and volume will differ

somewhat, but the principles of training remain the same.

In my mind, there are three well-known triathletes whose accomplishments suggest

they were able to find the balance between volume and intensity for racing at

Olympic and Ironman distances.

Mark Allen: it took him several tries at the Ironman distance, but Mark was one of

the fastest Olympic Distance racers in the world and accomplished at the Ironman

distance with the fastest Hawaii Ironman from 1989 until 1996 (8:09).

Luc Van Lierde: the Belgian was one of the fastest Olympic distance racers in the

world in the summer of 1996, the same year he set the new Hawaii Ironman record

of 8:04 (and that included a 3 minute penalty!).

Karen Smyers: in 1995, she won the Hawaii Ironman and four weeks later won the

women's ITU World Championships, Olympic Distance, in Cancun, Mexico.

The bottom-line? Olympic Distance and Ironman training are not necessarily

mutually exclusive during the same season. The principles of training aerobic

capacity are the same, but the balance of intensity and volume at a given time

during the training cycle is shifted.

Training Stress, Recovery and Adaptation

An important piece of the puzzle is the balance of training stress and recovery to

allow the body to adapt to increased volume or intensity. As described above,

periodization integrates recovery throughout the training cycle. Below is a graph

illustrating physiological adaptation to a training stress when adequate recovery is

facilitated. It also shows how that response may vary for optimal, excessive and

inadequate training stress. Yakovlev uses the term supercompensation to describe

this adaptation.

Training places a physiological load on the body, resulting in fatigue and a decline

in performance ability. Improvement in performance can only occur with adequate

recovery. Inadequate training stress may bring only small improvement.

Overtraining requires excessive recovery and may not show any improvement.

Optimal training with adequate recovery results in improved performance abilities

due to the adaptive physiological/metabolic potential.

This model can be applied to all periods of the overall training cycle, whether an

individual workout, several days of building or longer periods of preparation. Of

course, one of the challenges of coaching any athlete is to find the right balance of

stress and recovery for each individual -- that's why coaching is as much art as it is

science.

Experience of the Athlete

The novice endurance athlete is better served by focusing initially on learning the

skills and gradually developing the aerobic capacity for the more modest endurance

events, e.g., Olympic distance or shorter. Intensity also needs to be constrained

until significant adaptation to training has occurred. Those skills and endurance will

be directly transferable to the longer distance as the body is able to adapt to

increasing volume.

For the more experienced and fit endurance athlete, the goal in training is two-fold.

First, significant training volume must occur within the typical low and moderate

intensities normally associated with endurance training. Second, higher intensity

training that addresses all of the physiological components of aerobic capacity must

be incorporated in a progressive, timely approach that allows for the highest quality

of training based on individual abilities. Both volume and intensity must be

tempered by planned rest and recovery. In this way, the probability of reaching

your physiological potential is maximized.

| TriDavid Coaching |